November 10, 2020

In a case relating to the “front kit” of one of Ferrari’s top racing car models, the Ferrari FXX K, the German Federal Court of Justice[1] has referred two questions to the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) for a preliminary ruling[2]. The questions throw into doubt the existence and validity of unregistered Community design rights (UCDR) in individual parts of a product.

The CJEU’s response could significantly impact the scope of protection of UCDRs and raises interesting questions as to whether the UK will choose to adopt the CJEU’s approach in relation to the planned equivalent design right to be introduced in the UK post Brexit.

Background

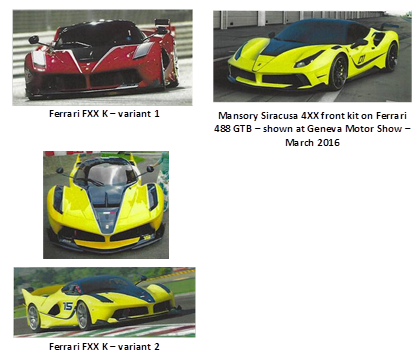

The Ferrari FXX K, Ferrari’s limited edition racing car, sold for €2.2 million, was first presented to the public by way of a press release on 2 December 2014. The car is available in two variants, one with the tip of the “V” on the bonnet painted in the basic colour of the vehicle with the rest of the “V” painted black, and the other with the full “V” painted black (see below).

At the Geneva Motor Show in March 2016, Mansory Design, a manufacturer and retailer of tuning components or “body kits” for Ferrari cars, presented a converted Ferrari 488 GTB under the designation “Mansory Siracusa 4XX” (see below). In this conversion, which transforms a €170,000 street model Ferrari to look more like the Ferrari FXX K supercar, Mansory’s V-shaped 4XX “front kit” (which comes in two variants with the V-shape either partially or completely painted black) replaces the original Ferrari 488 front panelling.

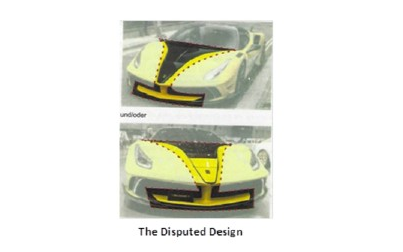

Ferrari was of the view that the V-shaped add-on front kit infringed a UCDR in its favour, said to be the combination of the V-shaped element on the Ferrari FXX K front hood, a central fin-like vertical element and a two-layer spoiler (the combination of parts identified in red dashed lines in the image below) (the Disputed Design). Ferrari contended that a UCDR in the Disputed Design and other part designs was created either by the disclosure of the vehicle itself or by the December 2014 press release or, at the latest, by the publication of a film entitled “Ferrari FXX K – The Making Of”.

Both the Lower Regional Court of Dusseldorf[3] and the Higher Regional Court of Düsseldorf[4] rejected Ferrari’s claim. They ruled that no UCDR existed in the Disputed Design because (1) the Disputed Design had not been originally disclosed or identified separately from the overall design; and (2) the Disputed Design was an arbitrarily defined sub-area of the overall design and did not have sufficient “independence” and “unity of form”.

The German Federal Court of Justice, taking the view that the Disputed Design was part of a complex product, seemed inclined to agree with the lower courts but made a reference to the CJEU regarding whether a UCDR can exist for components of a complex product (and the conditions under which such a right would arise).

CJEU referral

The German Federal Court of Justice asked the CJEU to interpret two Articles of the Community Design Regulation (Regulation (EC) No. 6/2002) by submitting two questions.

The first question seeks to establish whether an unregistered design of a part of a product is deemed to “have been made available to the public within the Community”, for the purposes of commencement of the three year period of protection, by disclosure of an image of the whole product, rather than by disclosing an image of the part on its own, or explicitly identifying the part within an image of the entire product.

If the CJEU rules that the answer to question 1 is no, design owners will likely be required to make separate explicit disclosures of each different part of the product in question at the time of first disclosure, much in the same way as is required to obtain registered design protection of a part of a product.

If the CJEU finds that disclosure of the whole product is sufficient to grant UCDR protection to a part of that product, the second question seeks to establish what conditions (if any) must be satisfied for the design of that individual part to have “individual character” for the purposes of validity of a registered or unregistered design. In particular, the German court asks whether the component part needs to establish in the perception of the informed user, an “overall aesthetic impression” that is “independent of the overall form” of the whole product.

An answer to the second question from the CJEU that imposes additional restrictions on the appearance of a component part will likely have signification ramifications on the validity of the thousands of registered designs already in existence for component parts of complex products.

The CJEU’s ruling is not expected to be handed down before the end of 2021.

Commentary

There is no question that a design, whether registered or unregistered, can exist in the appearance of a part of a product.

However, a ruling by the CJEU that the disclosure of an image of an overall product alone can only result in a UCDR for that product as a whole, is likely to have a significant impact on both design owners, who will be under a much greater burden at the time of first disclosure to individually disclose all possible parts of their product they may want to rely on in the future, and on IP practitioners whose common practice has historically been to identify the UCDRs relied on in an action by reference to the parts of the whole product which have been copied.

The German court’s view is that UCDRs should follow the same approach required in relation to registered Community designs (applications for which must clearly identify the part of the product for which design protection is sought) for the sake of legal certainty and to enable the interested public to reliably determine what is the subject of design protection. Whilst this makes sense in the context of registered designs, it arguably makes less sense in the context of unregistered designs, which are relied upon by fast-moving industries where the lifetime of the designs in question does not warrant jumping through the hoops required for registration.

With the end of the Brexit transition period fast approaching and the likely introduction of a “Supplementary Unregistered Design Right” from 1 January 2021, which is meant to replicate the UCDR in the UK, it will be interesting to see whether the UK courts feel obliged to follow any decision of the CJEU on this issue or whether they will diverge from any ruling of the CJEU that they do agree with.

In the absence of any agreed reciprocity between the two rights as yet, the temptation to move away may be considerable.

However, given that there is already significant uncertainty whether a design can enjoy UCDR if it is first disclosed outside the EU (but could have become known in the ordinary course of business to those operating in the EU in the relevant sector), further uncertainty regarding what exactly has to be disclosed is likely to cause additional difficulties for businesses who want to benefit from both the new UK “Supplementary Unregistered Design Right” and a UCDR.

[1] 30th January 2020, court ref. I ZR 1/19

[2] Case C-123/20 Ferrari SpA v. Mansory Design & Holding GmbH

[3] 20 July 2017, court ref. I-14c O 137/16

[4] 6 December 2018, court ref. I-20 U 124/17

Topics