June 27, 2022

Facts

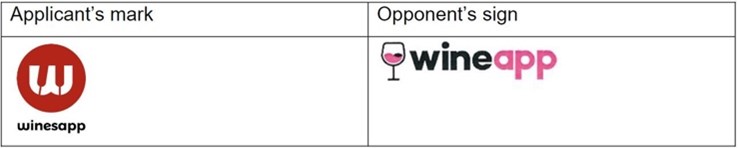

In September 2019, Benedict Johnson (the Applicant) applied to register WINESAPP as a figurative UK trade mark. Wineapp Ltd (the Opponent) opposed the application under s 5(4)(a) of the Trade Marks Act 1994, relying on its unregistered figurative sign for WINEAPP. Both signs are shown below:

The Opponent alleged that the Applicant’s mark and services amounted to passing off. It said that it had used its WINEAPP logo in its business since November 2018.

The IPO Hearing Officer dismissed the Opponent’s opposition and allowed the Applicant’s mark to proceed to registration. The Hearing Officer found that, on the evidence, at the application date of the Applicant’s mark, there was a small, but not trivial, amount of goodwill in the Opponent’s WINEAPP mark and that the mark was distinctive of that goodwill, but that there was no misrepresentation leading to deception or a likelihood of deception. Therefore, there was no damage.

The Opponent appealed to the High Court.

Decision

The Opponent said that the Hearing Officer had been wrong in her assessment of goodwill by failing to give sufficient weight to certain elements of the Opponent’s evidence and that if she had done so, she would have found that the Opponent’s goodwill was significant at the relevant date.

Mr Justice Edwin Johnson disagreed. In his view, the evaluation of the evidence was a matter for the Hearing Officer, and she plainly had all the evidence in the case, which was not extensive, well in mind. She had summarised that evidence, and then carried out an evaluation of it to determine whether the Opponent had established the required goodwill at the relevant date. There was no error of principle in the way that she had either approached or evaluated the evidence, and her conclusion was one that was entirely open to her. In any event, Johnson J agreed with the Hearing Officer’s conclusion, but noted that even if the evidence had struck him in a different way, he would not have regarded the Hearing Officer’s conclusion as one with which he was entitled to interfere.

The Opponent also said that the Hearing Officer had not correctly considered the decision in Lumos Skincare Ltd v Sweet Squared Ltd [2013] EWCA Civ 590, which establishes that, in certain situations, limited numbers of customers and sales can be sufficient to show goodwill to support a case in passing off. The Opponent argued that because Wineapp Ltd’s sales figures were higher than those in Lumos at the relevant date, the Hearing Officer should not have concluded that the sales figures were “low”.

Johnson J found that the Hearing Officer had not in fact found that the sales figures were “low”. She had found that the sales figures were “on the low side, but not a negligible sum”, which was not the same thing. In any event, the Hearing Officer was not required to make a direct comparison between the sales figures in Lumos and Wineapp’s sales figures. Wineapp’s sales figures had to be considered by reference to the market in which the Opponent was operating, and by reference to all the circumstances of the case, as established by the evidence. The Hearing Officer had correctly relied on Lumos as authority in relation to limited sales figures and goodwill and this reliance, which was in fact favourable to the Opponent, had been legitimate and not misapplied.

The Opponent also alleged that the Hearing Officer had failed properly to apply the guidance cited from Halsbury’s Laws (which she was entitled to use) in considering misrepresentation by not giving sufficient weight to the factors listed therein, which included that, at the relevant date, the Opponent had acquired significant reputation and goodwill in the WINEAPP sign.

Johnson J found that the Hearing Officer had made her evaluation of misrepresentation with the Halsbury’s guidance and the evidence firmly in mind. She had not gone wrong in her goodwill findings.

Johnson J also rejected the Opponent’s argument that the Hearing Officer had erred in wholly dismissing the verbal elements of the respective marks and failing to consider the signs globally. Analysing the Hearing Officer’s reasoning, he found that the Hearing Officer had considered the signs in the round and concluded, on the facts, that the distinctiveness of the non-verbal devices in the signs was sufficient to achieve the required distinctiveness between the signs, notwithstanding the virtually identical verbal elements. There was no error of principle either in the reasoning or in the conclusion drawn.

The Opponent also argued that the Hearing Officer had gone wrong in her finding that “consumers who are looking for wine recommendations will be inclined to see the shared word element as a coincidental use of descriptive language given the nature of the app and would rely on the device elements of the respective marks to distinguish between one wine app provider and another”. The Opponent said that there was no evidence of consumer behaviour, therefore there was no basis for such a finding.

Johnson J noted that the case was not one where it was said that there had been a course of dealing sufficient for the verbal element of the WINEAPP sign to have become so associated with the Opponent as to have acquired a secondary meaning descriptive of the Opponent’s services alone. That would plainly not be a tenable argument given that only ten months of dealing was relied upon. Therefore, the burden was on the Opponent to establish that the difference in the device elements of the signs was insufficient to prevent confusion in the minds of consumers. This might have been demonstrated by evidence from consumers, but no such evidence was adduced. Therefore, the matter was arguable on the available evidence only and the Hearing Officer could not be criticised for making her own judgment of likely consumer behaviour on that basis. She was entitled to do so, and in fact, it was an essential part of the decision required of her.

The Opponent also argued that the Hearing Officer should have concluded, pursuant to Office Cleaning Services Ltd v Westminster Window & General Cleaners Ltd [1946] 63 RPC 39, that there were no small differences in the respective verbal elements of the signs sufficient to avoid confusion.

Johnson J again disagreed. The Hearing Officer had decided that the verbal elements of the two marks were “virtually identical”, which was why, if distinctiveness was to be found between the two marks, viewed globally, it had to be found in the non-verbal devices of the signs. This was precisely what she had done. Her judgment on distinctiveness could not, therefore, be faulted.

Johnson J also rejected the Opponent’s argument that the Hearing Officer had failed to make a qualitative comparison between the device elements of the signs. .Johnson J found that the Hearing Officer had made such a qualitative comparison and it was precisely this comparison that had led her to conclude that there was no misrepresentation because there was sufficient distinctiveness in the non-verbal device elements of the signs.

Finally, Johnson J disagreed with the Opponent that the Hearing Officer had been clearly wrong in her conclusions overall. There had been no error of principle or law made. In any event, he agreed with the Hearing Officer that, overall, the Opponent’s opposition to the trade mark application should be dismissed. The appeal was dismissed. (Wineapp Ltd v Benedict Johnson [2022] EWHC 620 (Ch) (21 March 2022) — to read the judgment in full, click here).

Expertise