September 20, 2022

Facts

On 10 January 2019, Owen Jones tweeted the following, referring to an incident in which an egg had been thrown at Nick Griffin, the former leader of the British National Party:

On 3 March 2019, the former Leader of the Labour Party Jeremy Corbyn MP was assaulted with an egg whilst visiting the Finsbury Park Mosque. Shortly after the incident, the television presenter Rachel Riley tweeted as follows (the Good Advice Tweet or GAT):

The GAT was a response to the attack on Mr Corbyn. Only a reader who was aware of the incident would have understood the reference from her use of the egg, and a rose to depict the Labour Party. It was seen 1.5 million times. People responded to it differently. Many interpreted it to mean that Jeremy Corbyn deserved to be attacked because he was a Nazi, while others understood it to mean that Owen Jones was a hypocrite as he was showing selective support for acts of violence (i.e., egg-throwing) against politicians according to whether he supported them or not.

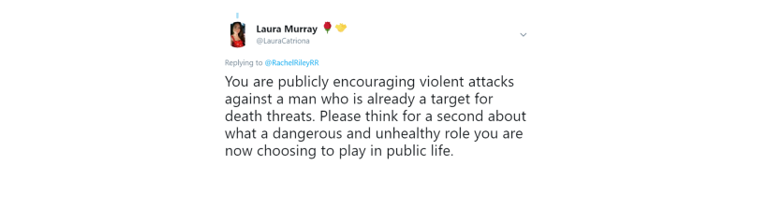

Laura Murray, who was the Stakeholder Manager for Mr Corbyn at the time, took the former view and responded to the GAT as follows:

Ms Riley did not reply.

Ms Murray then posted this (Ms Murray’s Tweet):

Ms Murray’s Tweet did not reply to, quote-tweet, or otherwise include the GAT, which meant that the GAT was not immediately available to anyone reading Ms Murray’s Tweet. The reader was therefore dependent upon Ms Murray’s description of the GAT to understand what it said.

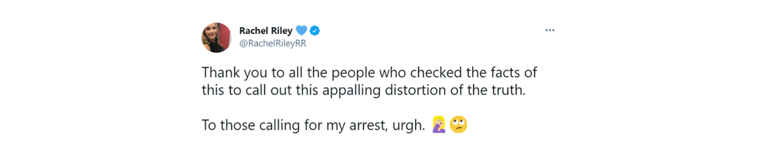

On 4 March 2019, Ms Riley responded to Ms Murray’s Tweet by quote-tweeting it as follows:

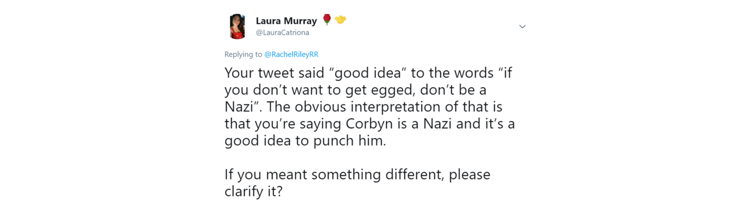

Ms Murray responded by saying:

Ms Riley did not respond.

Ms Riley issued proceedings against Ms Murray for libel in respect of Ms Murray’s Tweet. At a trial of preliminary issues, Mr Justice Nicklin found that the natural and ordinary meaning of Ms Murray’s Tweet was: (i) Jeremy Corbyn had been attacked when he visited a mosque; (ii) Ms Riley had publicly stated in a tweet that he deserved to be violently attacked (the Factual Allegation); and (iii) by so doing, Ms Riley had shown herself to be a dangerous and stupid person who risked inciting unlawful violence; people should not engage with her (the Opinion).

Nicklin J found that both the Factual Allegation and the Opinion were defamatory at common law.

In her Defence, Ms Murray denied that her Tweet had caused or was likely to cause serious harm to Ms Riley’s reputation. In the alternative, she said that the Factual Allegation was substantially true under s 2 of the Defamation Act 2013. She also pleaded that the Opinion was her honest opinion under s 3, and that her Tweet was a publication on a matter of public interest under s 4. Nicklin J accepted that Ms Murray’s Tweet was honestly published on a matter of public interest but found that none of the statutory defences had been established.

Ms Murray appealed Nicklin J’s rejection of the statutory defences. Ms Riley responded by requesting Nicklin J’s decision be upheld on alternative grounds.

Decision

Truth

Essentially, Nicklin J had found that Ms Murray’s Tweet was not substantially true because it failed to reflect the ambiguity of the GAT, i.e., that the GAT could be interpreted in different ways, as was shown by the evidence.

Ms Murray challenged this, arguing that if a section of respondents had understood the GAT to contain the Factual Allegation, then the defence of truth applied.

Giving the lead judgment with which the other Justices agreed, Lord Justice Warby upheld Nicklin J’s findings. The question, he said, was whether the ambiguity of the GAT made Ms Murray’s Tweet substantially true. What had to be proved true was the single defamatory Factual Allegation conveyed by Ms Murray’s Tweet. Nicklin J’s finding that the GAT did not make such Factual Allegation could not reasonably be denied.

Nicklin J’s judgment made clear that the Factual Allegation was an imputation that Ms Riley had made an express statement; it did not encompass a possible implicit meaning to similar effect. It was clear that the Factual Allegation was not literally true. The finding, that the GAT could reasonably be interpreted as conveying two meanings, one of which was substantially similar to the Factual Allegation, did not establish the truth of the Factual Allegation.

In Warby LJ’s view, Nicklin J had applied the correct legal principles and was entitled to find as he had.

Honest opinion

Ms Riley challenged Nicklin J’s decision in relation to the requirement in s 3(3) of the 2013 Act that the statement complained of must indicate the basis of the opinion. Ms Riley said that the requirement was not met because the basis of the opinion indicated in Ms Murray’s Tweet, i.e., that Ms Riley had publicly stated that Mr Corbyn deserved to be violently attacked, which was factual in character, was untrue.

Warby LJ rejected Ms Riley’s arguments, finding that the only question raised by s 3(3) was whether the statement complained of indicated the basis of the opinion which it contained. This was a question of analysis that turned exclusively on the intrinsic qualities of the statement complained of. If the statement did not indicate the basis for the opinion the analysis would stop there, and the defence would fail. If it did, the condition would be met, and the analysis would move to the next stage. The extraneous question of whether the matters said to be the basis for the opinion were true or false was immaterial at this stage of the analysis. To find otherwise would depart from the common law structure on which s 3 is based and introduce obscurity and complexity which was the opposite of the intention of the legislation.

Ms Murray challenged Nicklin J’s findings in relation to s 3(4)(a), which requires a finding that an honest person could have held the opinion based on “any fact which existed at the time the statement complained of was published”.

Warby LJ rejected Ms Murray’s arguments. The Opinion that had to be defended was that “by so doing the claimant has shown herself to be a dangerous and stupid person who risked inciting unlawful violence” and that “people should not engage with her”. “By so doing” was shorthand for “by publicly stating in a tweet that Jeremy Corbyn deserved to be violently attacked”. Warby LJ agreed with Nicklin J that the fact that the Opinion was expressly (and, in Warby LJ’s view, exclusively) premised on the truth of the Factual Allegation meant that the defence could not survive the failure of Ms Murray’s case on the issue of truth.

Public interest

Ms Riley challenged the decision that Ms Murray’s Tweet was on a matter of public interest, arguing that a narrow view of what is in the public interest should be taken.

Warby LJ rejected Ms Riley’s arguments, finding that the public interest is a broad concept. Ms Riley’s arguments were wholly artificial as she was not an unknown private individual and this was not a private chat with friends that had nothing to do with the public. She had used a public platform to address a readership, which exceeded that of most national newspapers, on a political topic. The matter of public interest that Ms Murray’s Tweet was about was the conduct of Ms Riley, a well-known celebrity and prominent political activist, in publishing to her hundreds of thousands of followers a provocative tweet relating to matters of political significance that were firmly in the public domain.

Ms Murray also challenged Nicklin J’s finding that her belief that publication was in the public interest was not reasonable.

Warby LJ said that Nicklin J had clearly found that the Factual Allegation reflected one of the reasonable meanings of the GAT. Further, Nicklin J had decided that Ms Murray was aware of the ambiguity of the meaning of the GAT before she posted her Tweet, as she had read the reactions on Twitter to what Ms Riley had said in the GAT. Therefore, she knew that there were two alternative interpretations of the GAT. Reading the judgment as a whole, Nicklin J was entitled to conclude that Ms Murray ought reasonably to have appreciated the ambiguity and that it was unreasonable for her to believe that it was in the public interest to characterise the GAT as she did, and to express the opinion she did, when it was obvious and should have been apparent to her that a different and much less damaging interpretation of the GAT was available. That conclusion was unassailable given his factual findings, which were not impugned.

The appeal was dismissed. (Rachel Riley v Laura Murray [2022] EWCA Civ 1146 (11 August 2022) — to read the judgment in full, click here).

Expertise