Contact

September 27, 2021

Facts

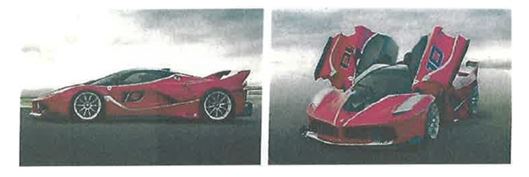

Ferrari Spa, the famous Italian racing and sports car manufacturer, first presented its top-of-the-range FXX K model, which has not been approved for use on the road and is intended to be driven solely on the track, in a press release on 2 December 2014. The press release included the following photographs:

The car exists in two versions distinguished solely by the colour of the “V” on the bonnet. In the first version, as illustrated by the photographs above, the “V” is black apart from its low point, which is the same colour as the basic colour of the vehicle. In the second version, the “V” is entirely black in colour.

Mansory Design & Holding GmbH specialises in the personalisation (known as “tuning”) of high-end cars. Mansory has been producing and marketing sets of personalisation accessories (known as “tuning kits”) since 2016. The tuning kits are designed to alter the appearance of the Ferrari 488 GTB (a road-going model) to make it resemble the appearance of the Ferrari FXX K.

Mansory offered five different tuning kits for various parts of the car, including a “front kit”, of which there were two versions reflecting the two versions of the Ferrari FXX K.

Ferrari issued proceedings against Mansory, in Germany, claiming that Mansory’s “front kits” infringed its unregistered Community design right (UDR) in the appearance of the part of its FXX K model consisting of the V-shaped element on the bonnet, the fin-like element protruding from the centre of that element and fitted lengthways (the “strake”), the front lip spoiler integrated into the bumper and the vertical bridge in the centre connecting the spoiler to the bonnet.

At first instance, the German court dismissed Ferrari’s claim. Ferrari’s appeal was also rejected on the basis that Ferrari had not shown that the minimum requirement of a “certain autonomy” and a “certain consistency of form” of the part of the vehicle making up its claimed UDR had been satisfied. The court said that Ferrari had merely referred to an arbitrarily defined section of the car.

Ferrari appealed to the German Federal Court of Justice, which has referred two questions to the CJEU on the conditions necessary for the appearance of part of a product to enjoy protection as a UDR under the Community Design Regulation (6/2002/EC).

Opinion

Advocate General Saugmandsgaard Øe noted that the appearance of only a part of a product can be the subject of UDR under Article 3(a) of the Regulation. To qualify, it must have been made available to the public under Article 11(2).

Given that Ferrari had only published an overall view of the FXX K model in December 2014, the German court has asked the CJEU whether, in order to satisfy the “making available” requirement under Article 11(2), Ferrari ought to have made available separately the design of the part of the bodywork for which it claimed protection.

The AG noted that Article 11 does not contain any specific rule on the “making available” of the design of a part of a product. Article 11 only refers to one criterion, namely that the design has been “published, exhibited, used in trade or otherwise disclosed in such a way that, in the normal course of business, these events could reasonably have become known to the circles specialised in the sector concerned”.

The AG said that there was nothing in the wording of Article 11 to exclude the proposition that publication of a single image could amount to the making available of the design of a product in its entirety and that of the design of the parts of that product.

The question was therefore whether the “specialised circles” referred to in Article 11(2) could reasonably have become aware of the UDR claimed. In the AG’s view, for this to occur, the part of the product claimed must be “clearly identifiable”, in the case of a photograph “clearly visible”, at the time the design is made available, and this case provided a good example of when this would indeed be the case. The photograph showing the front view of the FXX K revealed clearly the appearance of the bonnet and the spoiler of the car, including the V-shaped element on the central part of the bonnet, which made up the claimed UDR.

The referring court has also asked the CJEU about the legal criteria to be applied when examining individual character under Articles 4(2)(b) and 6(1) in order to determine the overall impression produced by the design of a part of a product.

The German appellate court had found that Ferrari’s UDR was non-existent as it did not have “a certain autonomy” and “a certain consistency in form”. The AG understood these expressions, which are references to German case law, to refer to cumulative conditions for claiming a UDR in the appearance of a part of a product. The “autonomy” condition referred to whether the appearance of the part was distinguished from or completely lost in that of the product as a whole. The “consistency” condition concerned whether the partial design claimed constituted a complete assembly. The two conditions aimed ultimately to determine whether the appearance of the part of a product claimed presented an “autonomous overall impression by comparison with the overall form”.

The question was therefore whether the appearance of a part of a product must also have “autonomy” and “consistency”.

In the AG’s view, the answer is to be found in the definition of “design” in Article 3(a), which refers to the lines, contours, colours, shape, texture and/or materials of the product and/or its ornamentation; the question was whether “autonomy” and “consistency” should be added to this list.

The AG said that he would be reluctant to introduce unwritten criteria into the definition. Irrespective of the fact that those criteria were not envisaged by the EU legislature, it was difficult to imagine how they would be capable of enhancing legal certainty.

In the AG’s view, the CJEU should simply apply the criteria in the definition of “design” in Article 3(a). The part of a product should therefore be defined by its appearance, consisting of its lines, contours, colour, etc., and be identifiable as a design. In other words, it must be capable of producing, in itself, an “overall impression” and should not be completely lost in the overall impression produced by the product.

The AG said that it was for the national court to ascertain whether the UDR met the definition of “design”. In the AG’s view, it did as it represented a section of the vehicle that was visible and defined by lines, contours, colours and shapes, which could be perceived as a whole. The court then needed to ascertain whether the design satisfied the conditions for protection as a UDR. To determine the overall impression for the purpose of assessing either “individual character” or infringement, the court must consider the appearance of the part alone, independently of the overall impression produced by the product as a whole.

The AG therefore opined that Article 11(2) should be interpreted as meaning that the making available to the public of the full design of a product, such as the appearance of a vehicle, also entails the making available to the public of the design of a part of that product, such as the appearance of certain elements of the bodywork of that vehicle, provided that the design of the product part is clearly identifiable at the time when it is made available.

Further, Article 3(a) should be interpreted as meaning that a visible section of a product, defined by its lines, contours, colours, shape or texture, constitutes the “appearance of […] a part of a product”, within the meaning of that provision, which may be protected as a UDR. There is no need, when assessing whether a given design complies with this definition, to apply additional criteria such as “autonomy” or “consistency of form”. (Case C-123/20 Ferrari SpA v Mansory Design & Holding GmbH EU:E:2021:628 (Opinion of Advocate General) (15 July 2021) — to read the Opinion in full, click here).

Expertise